Northerly winds, warm to hot days, and daybreak at 5am; expect longtail or northern blue tuna to put in an appearance in south Queensland waters. Despite being scarce over the last two summers, due to the massive floods, the very clear inshore and near coastal waters have ensured the tuna are back to their old haunts.

However, tuna are hard to take with fly tackle. They are common enough in Moreton Bay and off Southern Queensland waters, but as the weather warms they tend to be mighty touchy and not at all inclined to allow a boat within the 30m, which is necessary for the fly angler. Likewise, when hooked they have huge reserves of stamina and sheer doggedness that require a lot of angler’s effort to bring them to the boat.

All these points make them a very worthy opponent on fly.

The first step on the road to success is to be on the water as early as possible. Tuna have small gullets and don’t take long to fill up with tucker once they get into the bait. Find fish feeding as early as possible.

As a general rule, the birds are the signposts in the sky. You’ll find them hovering over a school of feeding fish.

However, where the fish will be is totally unpredictable. In Moreton Bay I’ve seen tuna everywhere from the jetty at the Wellington Point boat ramp right through to the beach off Moreton Island. At Bribie Island they can be in the eastern part of Pumicestone Passage. Anywhere in blue water just behind the surf break is the norm.

Unfortunately, tuna travel far and wide and therefore so must the angler.

Be aware that mackerel may also be present. It’s not hard to differentiate between the feeding tactics of the two species: macks tend to slash into showering bait without showing much of their bodies at all, usually while making some neat rooster tails on the surface, while tuna usually show their backs or tails as they roll into the bait with mouths working.

If on approach to a school with birds dipping and diving busily, you see flashes of silver, wide tails exiting the water from time to time or even the sight of a fish coming half out of the water within the melee, it’s a near certainty that tuna, not mackerel, are on the job.

It’s at this exact point where a lot of anglers go wrong. At the tantalising sight, the temptation to hit the boat’s throttle to get as close to the fish as possible before the action tapers off becomes too much and then, as the boat moves up swiftly, the fish usually shut down. A quiet and unobtrusive approach as possible will work best. Reduce the throttle to slow walking pace about 70m from the action, slowing even more when closing in on those last vital 40m.

Even if the school moves off of it’s own accord, so the long as the boat has been approaching gently without too much fuss or slap from the hull there’s every chance that the tuna will soon return to the surface nearby and offer another opportunity for a hook up.

Cast into a school that’s still working. Once the fly is where the chops and swirls are thickest, a quick retrieve should see the fly pull really tight for a second or two before the rod is almost pulled from your hand and the reel starts to spin as backing exits the guides.

At this point there is nothing for it but to let the fish go, easing the drag further as more and more backing is taken. At a certain point the tuna will stop, although the beat of his tail can be easily felt. Now comes the hard part, physically hauling that hard pulling tuna back to the boat. Keep the rod low, with the butt doing most of the work. The rod’s tip should only take the impact out of sudden lunges or spurts of power.

At a certain point the tuna will usually decide that he wants to circle under the boat for a spell. And that’s just what he’s doing; having a spell. With those wide pectoral fins extended and the big tail beating to a subdued rhythm, a circling tuna is a resting tuna and one that is going to take a lot more effort to finally bring boat side.

Easing the drag and then driving the boat off for a 100m will drastically change the angle of strain on the fish and stop the circling straight away. At this point, increase pressure, get the rod back into the picture and start retrieving in a pump and wind process. Once the tuna starts to show on the surface it’s close to end game. There may be a few more hard lunges or quick bursts of power near the boat but a surfacing tuna is a tiring tuna.

Net or gaff? Release or eat? It’s the angler’s choice but if it’s the latter the fish should be bled quickly as possible and iced down for best keeping.

Our coastal tuna can range is size from 6-10kg or more so there’s not much point in tackling them with lighter gear; unless you like to waste a lot of time, and inevitably a shark will join the party sooner or later.

A 10wt outfit is ideal, with an intermediate sink rate clear fly line set up on a large arbor reel (with a smooth drag system) holding at least 300m of backing.

The leader needs to be just less than the length of the rod to avoid issues with fly line to leader knots when the fish is beside the boat. Keep the final tippet strength to around 7-10kg, depending on the experience of the angler and just how wary the fish are on the day.

Choice of fly comes down to a derivative of the Leftys Deceiver or a Surf Candy. Tied on a size 1/0 or 2/0 hook it should be reflecting small flashes of silver to represent a baitfish. A hard feeding tuna is not a terribly fussy creature, so long as the fly has a fishy profile with some flash about it and is being retrieved rapidly.

Reads: 2093

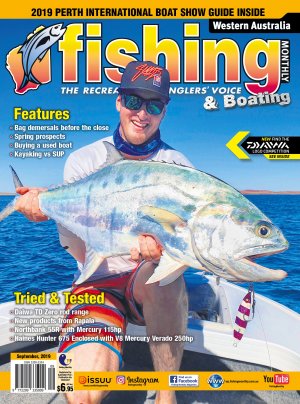

Long tail tuna, like the one the author is holding, are challenging fly rod opponents.

Flies for tuna need to have a baitfish-like profile and flashes of colour to invite attack.