I RECENTLY suffered a dramatic experience involving a fire on my boat. The vessel, a 4.92m Clark Abalone, burnt and – we assume – eventually sank.

Our location was Fog Bay, about 130km from Darwin, and we were about 8km offshore when the accident happened. I had noticed a strong petrol smell and stopped the boat. I inspected the two tote tanks for leaks and they were OK. We looked under the front deck and saw raw fuel in the bilge. There was obviously a crack or fracture in the 75L underfloor fuel tank.

I turned off all electrical equipment (GPS, sounder) to reduce the risk of sparks, and decided to soak up the fuel with towels and isolate the leak. But when I turned off the battery isolator there must have been a spark because, before I was able to do anything else, there was a ‘whoosh’ and fire burst out of the front and rear of the boat.

The fire quickly got out of control, and when my mate went to get the life jackets he had a sudden burst of flame past his head. He decided then that it was time to go overboard. I made a second attempt to get the life jackets from the front of the boat, but they were already on fire and melting.

In desperation, I threw our EvaKool 120-litre esky overboard to give him something to hang on to. The esky had 14 litres of water in bottles and some soft drink and food and ice.

I was able to retrieve my flare container, but by this time it had also started to melt. Fortunately the inner contents were okay, but as the container hit the water the emergency spare torch and a couple of other items floated out through a hole caused by the fire. The flares were saved.

I then went to get the EPIRB and some hats, but the flames became so intense that I had to jump overboard, thinking that the boat was about to explode. I didn’t retrieve EPIRB.

We paddled the EvaKool away from the boat quickly to avoid any chance of being burned. We watched the fire become so intense that the aluminium began to melt. We are sure we also saw a ball of flame blow out through the bow. The boat didn’t explode though. It burned for a good hour and then we lost sight of it.

We were out of sight of land, but we were fortunate in that the accident occurred in the morning and we were able to use the rising sun to guide us as we paddled east. We hoped that someone had seen the billowing black smoke and flames. Fog Bay is an isolated place and we had only seen one other vessel leave in the morning, and they would have been some 20km away when the boat went up.

We paddled the EvaKool constantly for about five hours before we spotted land on the horizon. This gave us a definite navigation point to aim at. We continued paddling, each of us holding onto one of the handles either side of the esky.

By about 8pm that night – 11 hours after we first went in the water – we were able to make out lights on the shoreline. This was encouraging, and when night fell we lay on our backs and kicked using the stars as a nav tool and keeping the lights on track. At sunrise we could make out some shacks on the beach, and at 8.30am we found that we were about 300 metres off a small headland.

At this point the tide changed and we were dragged back offshore for about a kilometre or so. The tides over the two days were from 7.3 metres down to .02 of a metre. Being dragged out to sea after paddling for nearly 24 hours was nearly the last straw and could well have seen the end of us.

We were in a state of confusion by this stage and were suffering from severe sunburn and exposure. It was pointless trying to defeat the tide change so we maintained our paddling to keep a steady station. We were fortunate enough to move only up and down the coast from this point, and didn’t go much further out to sea. It was extremely frustrating to see land so clearly but not get there. At no point did we even consider letting go of the icebox to swim for it. We would have drowned.

We saw a vehicle on a beach some distance away around lunchtime, so we let off three flares. We saw the vehicle leave the beach just after this so we assumed that they had seen our distress call. But it did not return, and no help came.

I judged the turn of the tide to be about 2pm in the afternoon, so at about 1pm we intensified our kicking and our one-armed paddling to cut an angle across the tide to hopefully gain some distance toward shore. This effort improved on slack tide and we were able to get within the same position as we were in six hours beforehand.

With the tide change came a change of wind direction and a slight increase in the swell. We used this to our advantage and angled the EvaKool so as to use the wind and swell to help push us closer to land. This worked, and at about 3.30pm we were able to come in over an exposed reef area. Fortunately for us we were then able to feel the bottom. After another half hour we could nearly walk, but the mud was so soft it was near impossible.

Finally we came on a sandbank and solid ground in about a metre of water. This was the most exhilarating feeling I have ever experienced and I became quite emotional. Unfortunately the sandbar was short-lived and we found mud again. The seven-metre tide was coming in so fast that it changed the sand/mud bottom into soft, oozy mud.

We eventually reached shallow water and then had to breaststroke in a fashion across the mud for a further half hour or so. At no time did we let the esky out of hand’s reach. We used our heads and hands to push the esky ahead of us as we slid like crocodiles across the mud.

At around 4.30pm we reached shore. Even then the tide was still rising so we dragged the esky up to high ground and collapsed. For the past 31.5 hours we had not stopped paddling or moving some part of our bodies.

After a little while, and after drinking lots of water, we made an effort to walk the estimated 15km to where we had first launched the boat at Dundee Beach. After about 2km we came across a chap in a four-wheel-drive. This was the second great feeling I have experienced. He took us back to Dundee beach to where my vehicle was.

We made the hospital the next day, and were immediately placed on drips and were attended to.

The EvaKool had saved our lives. It was buoyant, stable and maintained water tightness the whole time. The fittings are so well constructed that it enabled us to hang on without fear of losing grip.

We experienced some interesting things through the night at sea. We were shadowed for several hours by something big. It was clearly visible in the phosphorescence. As it swam around us we both made no mention of it and did not discuss it until we were recovering in hospital.

My mate had a metre or so shark come between his legs early in the morning before sunrise and this action grazed his legs through his trousers. It then proceeded to give him a whack in the back. We were visited by mackerel and other pelagics, and were stung by stingers and other types of jelly fish. At one point a Portuguese man-of-war (bluebottle) swam between us without incident.

To top it off, the beach where we made land has a small creek (and not far from the Finniss River that’s famous for the Sweetheart Croc) that has a 4.6-metre croc come in on the evening tide. One can be lucky right up to the last minute. – Ross Abraham.

[FACT BOX]

The Moral of My Story

• Carry plenty of water and drink small amounts every hour or so

• Take your esky or other floatation device with you

• Have a grab bag that has all safety gear in it close to you in the boat

• Have an EPIRB on you (mine was the larger older type mounted on the console)

• Hang the expense and put a spare EPIRB in the grab bag

• Make sure the lifejackets are either on or next to you and not tucked away up the front for convenience.

• Never panic and ignore thoughts of animals that might be sharing the water with you

• Don’t overexert yourself – just maintain a steady pace in the water

• Don’t fight the tide. Use it to your advantage

• Learn some basic navigation (such as using your watch as a compass) and don’t rely on electronic aids. Our experience in the sea scouts and land scouts over 40 years ago helped save us

• Know your stars and use them to your advantage at night

• Carry a hand-held compass in your grab bag

• Put some thin rope with spliced ends in the grab bag to attach to the esky in case of hand hold problems

• Most flares do work when wet (as we experienced)

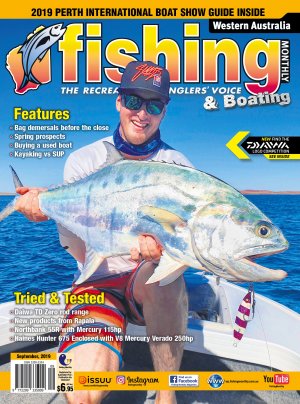

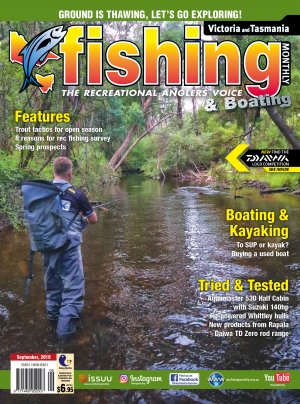

1) The survivors and the icebox that saved their lives.

2) When the boat burst into flames the PFDs were inaccessible, leaving the icebox as the only option.

Reads: 1058