I gave up on the New Year resolution idea when I realised that anything I found important enough for making promises to myself (like going on that fishing trip to the Austrian Alps) were best dealt with close to the time. If a resolution could wait until the beginning of the following year to take effect, then how important could it be?

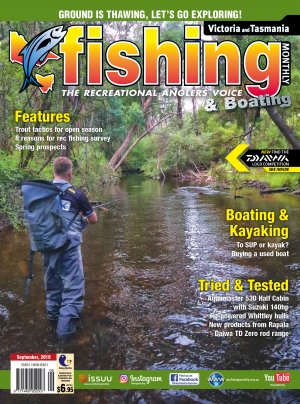

But the arrival of the New Year does make me a little reflective. Every year before Christmas, two life-long friends and I go fishing with our respective fathers. What began as a randomly chosen holiday to the streams of northeast Victoria has become an annual event, missed only once in 2003 because – ironically – of the birth of my son.

Our most recent trip was lots of fun as always, despite heavy rain curtailing many actual fishing opportunities. But the ‘Dads Trip’ has long ceased to be about the catching alone. For example, this year, a member of the party who shall remain nameless forgot the gas cooker, leading to many creative – and sometimes hilarious – efforts in the camp kitchen.

It is remarkable how much sheer happiness and satisfaction can come from a simple bush holiday. Often it’s the little things that glow warmly in the memory long after the event… swimming in the camp-side pool on a hot day, an echidna waddling unconcernedly between the deck-chairs, a fine evening meal conjured from a seemingly hopeless selection of ingredients, or just a good fire on a rainy night.

There’s no doubt about it, whether it’s an afternoon at the local jetty, or a long trek to a remote Bogong High Plains stream, one of the most precious things fishing offers us is simply the opportunity for outdoor adventure. Yet in 2005, it seems outdoor adventure is something our increasingly urbanised society finds in short supply – and, in fact, actively discourages. Partly, this is because a large number of Australians now lead lives so detached from the natural world, they are utterly helpless in it.

When my Dad was growing up in suburban Melbourne, he still enjoyed bike trips to the wilds of Templestowe and Dandenong, where he and his friends went rabbiting and fishing. Scarcely a generation later, it seems the typical Aussie is now more like a visiting Londoner I once took to Point Addis beach, who stood dumbstruck as a wavelet came gently up the sand and soaked her best shoes. Having never walked beside the ocean before, the pulse of the sea was beyond her comprehension.

Every week, our newspapers carry tales of unfortunate souls who have wandered off into the snow in sandals, have drowned in rivers small enough to paddle across, or fallen from cliff-tops they should have been nowhere near. Usually, these tragedies then see passionate calls to fence off the rivers or ban people from walking more than a hundred metres from the park kiosk. Almost as sadly, sometimes these calls succeed. In a society that carries a dread of being sued for another’s stupidity, while simultaneously detaching itself from the concept of personal responsibility, freedom for outdoor adventure is stifled.

In a pincer movement, the bureaucrats and environmental fundamentalists come in from the other side, closing access tracks, shutting campgrounds and designating ever-multiplying areas where fishing is not allowed. Often the threats to fishing slip by almost un-noticed – a water corporation quietly applying pressure to prevent fish stocking in a lake, or the introduction of a permit system that greatly restricts camping in a favourite National Park.

But in an interesting parallel development, the social value of outdoor pursuits like fishing, is gaining recognition that extends beyond mere economics. So at the same time as access to outdoor adventure is being directly or indirectly curtailed, it is also being broadly recognised as critical to overall health and well-being. For example, the epidemic of childhood obesity in western societies is regarded as due, at least in part, to an immobile lifestyle – one where computer games are more familiar than fishing rods. Meanwhile, an increase in the incidence of myopia (short-sightedness) in city children is being blamed on a lack of open space necessary for healthy eye development.

But perhaps most striking, clinical psychologists have now recognised the value of the outdoors to good mental health. Recently the ABC’s 7.30 Report carried a story about psychologist Dr Simon Crisp, and his successful efforts to treat chronically depressed or dysfunctional teenagers using what he called ‘Adventure Therapy’. Dr Crisp not only praised the value of outdoor adventure in mental healing, but also flagged the lack of it as the likely cause of much unhappiness in modern society.

Now, the typical reader of VFM doesn’t need a psychologist to explain the contribution fishing makes to their quality of life. Nor, I am sure, did my Dad in 1968 have to read some article about the benefits of outdoor adventure, to know intuitively that it was a good idea to take his six-year-old down to the Delatite River to chase trout. Even if it did mean more time baiting my hook and untangling my line than actually fishing himself!

However, I do think that at times we take for granted just how precious and irreplaceable fishing is. In the face of those who would take away fishing opportunities big or small, directly or indirectly, we need to remember what we stand to lose.

Reads: 1033