As I write, the dreaded weed continues make its most unwelcome presence felt along Fraser Island’s ocean beaches. During the latter weeks of October, there were periods of optimism followed with despair. Hopefully this month will be the end of it. In response to many enquiries about the dreaded weed, and in an attempt to find some answers, I have written a short article. Look out for it at the end of this area report.

Now that water temperatures in Hervey Bay are up to expectations, we should see plenty of action on the shallow reefs and along the deeper ledges and holes this month. The increased abundance of reef species is probably because many of the reef dwellers become more active and feed in warmer summer conditions.

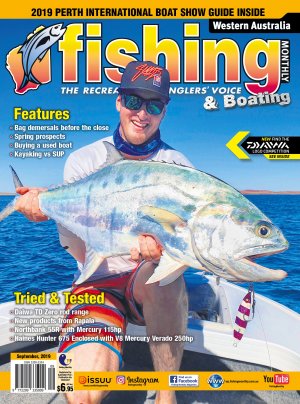

At this time of the year, my column usually includes a run-down of the various species that are available, as well as where, when and how each might be targeted. This month, I’d like to feature just one of our favourites – the blackspot tuskfish, Choerodon schoenleinii, or blueys as they are known locally. Although we can expect the best in coming months, there have already been encouraging reports.

Blackspot tuskfish are widespread across northern Australia and Southeast Asia. In Hervey Bay, they reach a serious weight of over 12kg. They’re without any dispute, kilo for kilo, the meanest fighting fish that Hervey Bay has to offer. It’s more than just their power – they have the dogged determination to find the cover that will break the angler’s heart.

You’re likely to find blueys on just about any reef structure throughout Hervey Bay. The larger fish, say 5kg+, are found on moderately deep reefs such as Moon Ledge, Rufus Artificial Reef, the Channel Hole and even the deep channel outside the harbour leading towards the pier. Although smaller fish around 3kg or less can also be caught in these deeper areas, most frequent the shallow reefs such as those around Point Vernon and Scarness, or along the northern and eastern shores of Woody Island.

Blueys feed by browsing the reefs for food, using their strong teeth effectively. They have a marked preference for crustaceans, particularly crabs. By far the best bluey bait is crab, similar to what it might be searching for. At Point Vernon and close to Woody Island, small black runner crabs and sleepy crabs are the best baits. These can be collected around any of the rocky foreshores.

I’ve used small paddler crabs on the reefs close to Scarness Beach and Round Island with success. Yabbies, soldier crabs and prawns work reasonably well, but being soft, are quickly taken by small fish. Most of the larger reef fish are also partial to crabs, so it shouldn’t be a surprise if you hook-up with a coral bream (grass sweetlips).

If the bigger fish are your game, you’ll probably be fishing one of the deeper ledges or the artificial reef. Set yourself up with at least 50kg mono handline, 4/0 to 6/0 Mustad Hoodlums, and sturdy gloves. Local experts use whole sand crabs (legal of course) or large blue-claw crabs collected from the foreshores. When a big bluey takes one of these, there’s no place for finesse. It’s a matter of not giving an inch. Get the fish away from cover as soon as possible.

If these big brutes are not to your liking, you might like to target smaller fish over the shallow reefs. Here we can expect fish up to 4kg with most around 1-2kg. It might sound like extreme overkill, but you need to load up to 22kg mono, and use 1/0 to 3/0 strong hooks. Of course the rod needs to be up to the task. My preference is for a flooding tide early morning or late afternoon, fishing along the edge of the hard reef. There is no room for finesse once a fish is hooked.

I must confess, I don’t have a good track record using artificials when targeting blueys. However I know that others are getting results on a variety of plastic look alikes and Cranka Crabs. This aspect of bluey fishing is on my to-do list. For the next five months, blackspot tuskfish should be plentiful in the shallows. On the deeper ledges and holes they can be caught throughout the year. The minimum legal length is 30cm, with a bag limit of five. As a coral reef finfish, the bluey would be a component of a combined bag limit of 20.

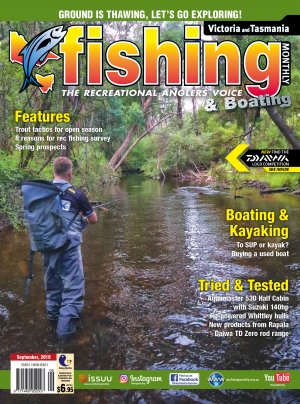

Weed, weed and weed – the horrible floating brown algae that effectively wiped out Fraser Island’s tailor fishing during August, September and much of October. What I have to say here is in response to anglers who have returned from the island with lots of frozen pilchards and very few tailor fillets.

I’ve been drawing on my own experiences over the last 50 years as well as what science is able to tell us. As you will see, there are far more questions than answers. Can we expect another wipe out in 2017? This is the most frequent question to come to me. Unfortunately, it’s a question I can’t answer and wish I could.

The culprit appears to be the macroscopic algae, Hincksia sordida. There have been suggestions that this is associated with bottom dwelling sea grasses, but these have generally been discounted in favour of the free floating algae undergoing rapid growth, forming the blooms that have occupied the inshore waters of Fraser Island’s beaches during these months. Studies have attempted to identify the factors that bring about the blooming of the algae. Nutrient levels, particularly those of nitrogen and phosphorus, appear to be involved.

The dreaded weed, as many like to call it, is by no means new to the island. My first encounter with it was in the mid sixties when an infestation covered the Waddy Point to Ngkaka Rocks Beach, as well as Middle Rocks and Indian Head. The problem really came into prominence when the main surfing beach at Noosa was infested during 2002 and continued annually until at least 2006.

Floating in the water, the weed was enough of a problem. When washed up on the beach, the resulting decomposing and stinking mass became a real health concern. Removal of contaminated beaches was one way of dealing with the problem, while fine mesh barriers were also given consideration. During those years, it was recognised that the origin of the weed was off the northern coast of Fraser Island, carried by ocean currents to be trapped in the Noosa beaches.

During that period of about five years, infestation by Hincksia sordida was a regular occurrence along Fraser’s ocean beach. Since then we have enjoyed almost a decade of freedom. Certainly there have been a few false starts in that time, but none developed into serious infestations. The origins of the blooms are related to the physical conditions of ocean beds, currents, rainfall, temperatures and the chemical conditions of primary nutrients, but the question of how and when all these factors come together is another matter.

Whenever we see some evidence of essential elements coming into play, we expect to see a lot of finger pointing. The obvious example of this is in the proposed effect of fertilisers and pesticides on the Great Barrier Reef. When we consider our current problem, we need to be reminded that Fraser Island and its neighbouring coasts are comparatively low contributors of pollutants into the ocean.

In considering more recent blooms, there have been suggestions that increased human activity could be making a contribution. I completely disregard this idea, as during the strong and widespread blooms of the sixties and earlier, there were very few people on the island compared with what we see today.

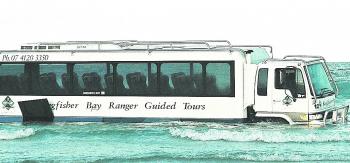

During an algal bloom event such as this year’s, much of the weed remains floating with small amounts washed onto the beach. However, when conditions are optimal as they have been at Noosa, large masses of weed come ashore. Quite often these are covered with wind blown sand, giving the appearance of a perfectly normal stretch of beach. This has been the downfall of vehicles seriously bogged after venturing over hidden, rotten weed. In 2003 on the southern side of Indian Head, the tourist bus went down so far that it became an almost impossible job retrieving it.

Just a week ago, to everyone’s delight, there was a clearance along the beach either side of Happy Valley. It looked as though it was all over. However, just a day or two later anglers at Poyungan Rocks reported it to be back again. How much longer it persists is another question. I have seen the problem go through to December, but that was decades ago.

At this point, I should mention some other nuisance weed events that can certainly frustrate anglers. One is the rather aptly named ‘snot weed’. Areas of this weed are not usually widespread and often form froth-like rafts. Fishers encounter it as jelly-like nodules on retrieved line. There have been suggestions that this is related to Hinksia sordida but I am not convinced.

The western beaches of Fraser Island also experience a weed infestation, but this is quite different to the Hinksia sordida of the ocean beach. During winter months, a number of plant species flourish in the shallow waters of Hervey Bay. During late winter and spring, seasonal northerly winds disrupt plants and eventually wash them ashore. Along much of inner Hervey Bay, particularly along Dundowran beach, various algal forms choke the foreshores.

Along Fraser’s western beach, most of the washed in plant life is sea grass. This is rolled in by wave action and ends up as piles of decomposing weed up to a metre thick. Breakdown of the weed takes place over a few months, returning nutrients to the beach. Unlike the dreaded weed of the east coast, the occurrence of weed on the western beach is fairly predictable, with at least some inconvenience in the latter months of each year, even into January.

The burning questions remain unanswered. Can we expect Hincksia sordida to return in next year and to what extent? It would be great if our marine science gurus could develop a tool to predict coming infestations. Unfortunately, this tech is a little way off.

Reads: 6384

A juvenile blackspot tuskfish.

The dreaded weed choking the surf zone and washing onto the beach.

The Kingfisher bus was bogged in the unseen weed.