It is an unfortunate fact that the best places to catch a feed of prawns in NQ are usually also the nursery grounds of some of our important inshore fish species. Prawns and juvenile fish congregate together in our estuaries and along adjacent beaches where waters are turbid from run-off and often carry a substantial load of flood debris during the wet season.

Locals know that the best time for prawning is during and just after the wet, preferably following a big flood. It is no coincidence that this is when juveniles of king threadfin salmon, giant queenfish, mulloway and several other types of commercial and sports fish are sharing exactly the same grounds as the prawns.

It is simple, the fish follow the prawns; juvenile fish follow juvenile prawns as well as the tiny Acetes prawns that can be found in huge numbers along many shorelines adjacent to estuaries.

Evolution has timed the reproduction of much estuary life to coincide with the abundance of nutrients flushed out of our rainforests during wet season floods. This surge of nutrients supplies a complex food chain, including a seasonal profusion of crab, prawn and shellfish larvae. These in turn are preyed upon by juveniles of larger inshore fish.

Unfortunately the most productive time for prawn netting happens to be when those juvenile fish are of sizes that become caught in the mesh of prawn nets. Once meshed, most small fish die before or during their extraction.

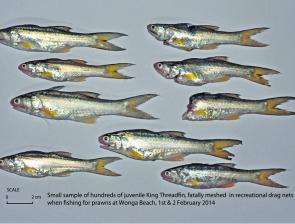

Regulations state that the stretched mesh size for drag nets must be no more than 28mm. The one I bought back in 2001 had a stretched mesh size of 14mm. It has proved so lethal for meshing fingerling threadies and queenies at Wonga Beach that I no longer dare use it during the wet season anywhere near our local estuaries. The risk of killing hundreds of these little beauties is just too great. Been there, done that: never again.

A friend and I went bait netting for garfish one night much later in the season, using his 28mm bait net. We ended up meshing and unavoidably killing about 30 juvenile giant queenfish for just a few gars in our one and only haul. This time the queenfish we meshed were about twice the size of those I had caught in the smaller mesh of my net earlier that year.

This is the problem with any small mesh net. By this, I mean any mesh size below a barra net will inevitably kill undersize fish. Used correctly by experienced operators, mullet surround netting is normally one general exception; but used without due care or as gill nets they will still kill significant numbers of undersized fish.

Dragging for prawns kills juvenile fish and even tiny prawns, which are too small to be caught in the mesh. This happens when flood debris, mostly broken up leaf litter and small twigs, accumulates in the base of the net, just above the lead line. Hundreds of juvenile fish and thousands of tiny prawns can and do become trapped in this debris which is compressed against the net. They quickly suffocate and die.

Depending on tides, the evidence is left on our beaches for all to see until dispersed by the waves. This may be just minutes on an incoming tide or a few hours on an outgoing tide.

There is no getting away from it, recreational prawning in North Queensland inevitably takes its toll on the juveniles of inshore species, such as the king threadfin, giant queenfish, silver and scaly jewfish shown here. The exception of course may be in areas that have already been heavily overfished.

There may have been a time when this was of very little consequence. In those days there were far more fish and far fewer people on our beaches, and very few of those people were chasing prawns. Now we have far fewer fish and far more people.

Human ‘progress’ has ensured there are also many other factors reducing both the numbers of mature female fish left to spawn and the survival rates from each spawning. It is now time to evaluate what is going on and decide whether our fish stocks can afford the continuing waste of fingerlings from recreational prawning.

Some claim the casualties caused by recreational prawn netting are miniscule in comparison to those inflicted by prawn trawlers. They note trawlers take huge numbers of small fish as by-catch, including threadfin, most of which end up dead. A closer look reveals there may be less cause for concern from an inshore point of view than appears at first glance.

So far I have not located records of significant numbers of juveniles of many of our large inshore species occurring as by-catch from commercial trawlers working offshore (in marked contrast to beam trawling in estuaries). Do let me know if I am missing something.

Threadfin have formed up to 1% of the offshore trawl by-catch in some published studies. However the threadfin involved is the small fast-maturing putty-nose threadfin (Polydactylus multiradiatus) not the mighty, slow growing, late maturing and inshore-living, king threadfin (P. macrochir).

Another common misconception arises from the fact that each adult female fish lays many millions of eggs. People assume there are bound to be so many millions of fingerlings that a few thousand being caught in small mesh nets in any one area is unlikely to have any effect. This overlooks the huge mortality of eggs and larval fish, which occurs in the wild, well before any individuals ever reach fingerling size.

While it would be difficult to make even reasonably accurate estimates of the proportion of the eggs surviving in the wild to fingerling stage, this may be approaching 0% of some spawning events under adverse conditions and even below 1% under favourable conditions.

In summary, once juvenile fish have reached fingerling size they have already survived the most hazardous stages of their lives. Their chances of reaching maturity should now be far higher than they were of reaching fingerling size in the first place, other things being equal (including the absence of recreational prawning).

Here is a question for anyone considering trying for a feed of prawns: Is the inevitable slaughter of juvenile fish worth the possibility of catching your bucket of prawns?

Put that question to any responsible fisher in the modern era and surely the answer must be a resounding ‘no’?

Small estuary systems like the Daintree have very limited nursery areas for the inshore species shown in the photographs presented here. Fish stocks of such small estuaries, if regularly netted by the public for prawns, will be impacted more heavily and much sooner than some of the larger systems further south, depending of course on the amount of recreational prawning done in these systems. It is all relative.

There are many factors adversely impacting our ever-declining inshore fish stocks these days. We need to do what we can to halt this decline. Recreational prawning by the public could readily be discontinued with zero hardship to the perpetrators.

We have had some spirited discussion about this on Facebook at SustainableFishing (one word). Fishers for Conservation also have more information at www.ffc.org.au including a poster or flier discouraging the use of drag nets. You can download it for free from FFC at http://bit.ly/1gBxMAN. Professionally printed hard copies are available in bulk from me.

Since this poster was published I have learnt that cast nets are used intensively to target prawns elsewhere. I am told they can also be responsible for significant kills of juvenile fish, especially threadfin, which die very quickly when in contact with any net.

Generally speaking though, most people would expect that cast nets used carefully by skilled, responsible anglers just to catch bait for a day’s fishing will have negligible impact in comparison to targeted cast netting for prawns.

Just because it is legal to drag nets up and down the beach through prime fish nursery grounds for hours on end, killing thousands of juvenile fish, does not mean it is the right thing to do.

This topic is just one of many cans of worms requiring scrutiny by the long-awaited review of Fisheries Management in Queensland. – David Cook

Reads: 3829

David with by-catch from just one prawn drag net haul left on Wonga Beach: 203 juveniles of four species, 87 silver mulloway, 84 jewel fish, 17 silver teraglin and 15 catfish. Most were between 4-7 cm in length.

Small section of a drag net with 10 fatally meshed juvenile king threadfin indicated by yellow arrows. At least 20 died in this trial four-minute drag by David and family. Hundreds of similar sizes were killed by prawn drag netters that weekend.

Sample of hundreds of king threadfin that died in prawn drag nets at Wonga Beach 1-2 February, average length less than 10cm.

A giant queenfish fingerling fatally meshed in a bait net; they become jammed in too tight to remove alive.