There has been a lot of talk about how many fish went over the Awoonga spillway, and even more talk about how many died. This has led to speculation about Awoonga as a fishery being finished. But I’ve heard different views and I’ve also heard of enhanced recreational opportunities in an around Awoonga.

With these rumours spinning around in my head, I thought I’d get to the bottom of it and find out, from the horses mouth, just what is going on at Awoonga, and what the future holds.

In late February, Steve Morgan and I made the trip up to Gladstone to meet with and discuss the situation with Gladstone Area Water Board’s (GAWB) Hatchery Manager Kurt Hutchby. Kurt has been at the coal face for years, has been responsible for stocking more barra than I’ve had breakfasts and is right in the firing line of those preaching ill tidings about Awoonga. He is also the guy working overtime to produce more barra, all while rescuing and releasing his share of those barra that went over the top (see QFM March 2011 issue) so that they may survive and provide recreational anglers an even more diverse range of fishing options if Gladstone and Awoonga are in your sights.

Lake Awoonga first started to go over the top in December of 2010. This event saw thousands of barra gather around the spillway wall, just waiting for a chance to follow the current down to the salt. It’s a natural barra instinct so GAWB staff were expecting fish to go over when the water depth was sufficiently high. This magic height was around 60cm above spillway level and Kurt and his team watched anxiously as the water level rose toward and then eclipsed the 60cm mark. As if on cue, barra started to go over the top, leaving Awoonga behind forever.

Unlike many other spillways, Awoonga’s spillway is particularly fish friendly. It is a gradual slope that ends in a scooped shape that meant the barra did not come to a crushing halt on sharp rocks, but rather sailed down the spillway and into the Boyne River. After the overflow height reached 60cm, it kept rising to a mammoth 4m, making it impossible to count the number of fish that went over. However, hatchery and GAWB staff have made estimates and they are certainly in the best position to do this.

As Kurt said, “We believe the number of fish that went over was around 25,000”. Now that’s an impressive number of fish, especially when it is estimated nearly all of these fish were over the magic metre mark!

While Awoonga was spilling hard, the fish distributed far and wide. Some fish are being caught at the mouth of the Boyne, some fish in the middle and some fish up in the freshwater reaches. These fish have been described as healthy and fit with many, many anglers reporting amazing captures of both numbers and size of barra that are typically freshwater-lake in build and colouration.

While all this was going on, persistent rumours held that there was a massive fish kill from the overflow event. Again Kurt and staff members were in the field assessing these rumours and found quite the opposite.

“At the first opportunity we got down to the spillway and the spillway outlet to see how many fish had died,” said Kurt.

“We found very few dead fish, which was a pleasant surprise, and we have estimated the number of fish that died from going over the top to be around 1500 only,” finished Kurt.

Let’s put that into perspective a little before we all gasp in shock that 1500 metre-plus barra died.

Awoonga has been stocked with over 3 million barra, of which around 40% are estimated to have reached maturity. That’s a staggering 1.2 million barra in Lake Awoonga of various sizes. From that number of fish, 25,000 escaped over the spillway wall and only 1500 died. In percentage terms that means about 2.1% escaped and only 0.13% of Awoonga’s barra died. Of those that went over the spillway 6% of the fish died, leaving a staggering 23,000 barra or so happily swimming around the Boyne River terrorising bait.

In the larger scheme of things, the breakout event was not such a big deal, but the images sprayed all over the internet forums and social media pages portrayed something that simply did not happen. It was typical snapshot hysteria where a moment in time is considered the truth for a much longer period.

I asked Kurt to explain further and he said that “to see a hundred metre-plus barra schooling up and then going over the wall is pretty impressive, but it’s not indicative of every minute of every day”.

“I stood on the spillway for over an hour at times and did not see a barra, let alone see one go over the top, so people have simply failed to recognise that barra after barra after barra did not go over the wall every minute of every day,” said Kurt.

Let us agree with Kurt’s numbers and move on to talk about the survival rates of the fish that went over.

Kurt had the opportunity to see first hand the dead and dying barra below the spillway. There is a 400m exclusion zone that nobody without a permit can enter, therefore Kurt and a select few assistants were the only ones in a position to truly assess the damage. What Kurt and the assistants found was a mass of catfish and barra, the likes of which have probably never been seen, milling around in the spillway pool directly below the spillway. This pool is at most 2m deep, runs the length of the spillway and is about 40m wide. It was estimated 2000-4000 barra were trapped there.

These trapped barra were not dying, in fact surveys carried out by GAWB staff and volunteers showed the barra were a bit scuffed, battered and bruised, but they were healthy and lively, actively chasing baitfish and feeding. And yes, the rumours of people fishing below the spillway were true. The only way Kurt and his team could assess the fish was to catch them on rod and reel and this became a big part of the health and stock assessment of the fish. The team would catch a fish, measure its vital statistics, check it for wounds and release it. In a few days time, the team then went back, caught some more fish and assessed how the fish were recovering. This happened until our trip, where we were lucky enough to be part of one of the last looks at the trapped fish and I can tell you these fish are exceptionally fit and healthy.

During the time from the first assessment of the fish numbers and health below the spillway, Kurt always knew when the spillway stopped flowing the fish would be trapped. Having never dealt with such an event before, it was a case of experimentation to see how they could ensure the survival of the fish.

Their first efforts were extremely labour intensive and involved angling individual fish and releasing them, via the hatchery trucks, into the Boyne River. Kurt tells me that four anglers fished until they literally could not hold a rod anymore and he said they didn’t even count the number of fish collected and released. This happened on several occasions until they all realised there just wasn’t enough hours in the day to catch and release all the barra. Time to think up another plan.

The second plan involved driving an excavator up to the rock wall penning the fish in and digging out four channels to allow the fish to swim to freedom of their own accord. This happened 5 days before we visited and while we were assessing the stock (that’s fishing for them!) we saw barra over a metre swim straight past us through the channels and escape down into the Boyne River. The smile on Kurt’s face said it all. The fish his team bred and released were going to survive, albeit in the Boyne and not Awoonga, but survive they would.

It was a master stroke of ingenuity and effort and any angler fishing the Boyne in the next few years should heartily give thanks to GAWB, Kurt and his volunteer helpers for giving them a shot at a true monster barra in a river situation.

But the other take home message from all this, is that over a million barra are still in Awoonga, just waiting to be caught. It’s not dead. It’s not barren of barra.

It’s definitely worth the trip to fish Awoonga, but now you have a secondary fishery in the Boyne to complement the wonderful fishery that Awoonga still is.

Everyone seems concerned about the future of Awoonga. It is a premier barra fishery and remains so, yet I have been given an insight into what is going to happen there over the coming years and I can’t wait until some of these plans come to fruition.

Let’s start with barra, as that is really why anglers travel to Gladstone, Benaraby and Awoonga. Two nights before we visited the hatchery, GAWB staff had spawned 1.8million barra. Say that out loud a few times to get your head around it. That is an incredible number of fish. These are excess fish that will be used to supplement stocking in various locations where numbers were short. The barra breeding process is effective and well managed at the GAWB hatchery. They can breed barra at just about any time they want by altering water chemistry, light duration and adding specific hormones at specific times. It seems there will be no shortage of barra being made available to Awoonga and other lakes south of Mackay in the near future. So tick off barra as continuing from strength to strength.

The next species is mangrove jack. This hard nut of a fish has been a hard nut to crack in regard to artificially spawning. They could induce the fish to spawn, but it was almost impossible to get the fry to fingerling size for release. I can happily report that GAWB staff now are able to get a 90% survival rate with mangrove jack. And that means a few select lakes will be heavily stocked with the red devils. As far as Awoonga is concerned, GAWB has a permit to stock up to 50,000 mangrove jack per year! For 10 years or more anglers have been awaiting this news and when I was told of the survival rate, I asked three times if the figure was right. It was and mangrove jack will be thick in a few lakes in the years to come. Now that’s a challenge I want to take up!

There are also plans to stock other species including sea mullet (150,000 per annum) and saratoga (550 fingerlings or 50 adults). The reasons for stocking these species are two fold: Firstly to provide biodiversity and secondly to provide angler opportunities.

So the future is very bright at Awoonga. The overflow event was not catastrophic. There are thousands upon thousands of fish still available in the lake and the Boyne River and surrounds have had an injection of some seriously big and nasty barramundi!

I wouldn’t hesitate to take a trip to Awoonga and Gladstone in the next few months. The fishing opportunities are unparalleled right now and will continue to grow in the years to come.

Special thanks must go to Kurt Hutchby and the GAWB staff who took the time to look after us, provide information where necessary and for making Awoonga a premier fishery by any standards.

Facts

Awoonga into 2011

When we visited Gladstone I made a point of talking to Awoonga’s top guide, Jason Wilhelm of Barramadness, about how he thought Awoonga would fish throughout 2011 as many are predicting its demise. He had no hesitation in saying that Awoonga will be every bit the fishery it was before the overflow event and that is good enough for me.

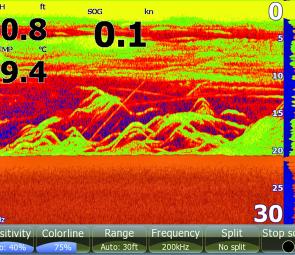

Jason worked hard with Kurt and members of GAWB to save the fish below the spillway, but he also spent hours on the dam sounding around and locating fish with his Lowrance HDS unit to assess fish numbers in the lake.

Jason said, “Boothy, I have never seen anything like some of the things we saw on the lake.

“There were barra stacked in aggregations down in 40ft as big as I have seen anywhere. Some of these aggregations extended up to 15ft deep.

“I could barely believe my own eyes and it’s a good thing that the sidescan makes it so easy to tell what the fish are,” said Jason.

He went on to add that he did not expect the fish to really come back onto the bite until the sediments and nutrients in the water had settled out, something that was happening while we were there. The sediment load down deep in the lake was above what hatchery staff believed barra would comfortably feed in and the nutrient load was adversely affecting the water chemistry also causing the barra to slow their feeding down.

The sediment and nutrient load is dropping out as the lake level approaches the spillway height and the lake’s current slows down. Jason believes that as soon as the spillway stops flowing over (this will happen in March some time unless more heavy rain is experienced), the water will clear and the barra will be out hunting.

Jason finished by saying that “Once the nutrients settle, along with the sediments and re-establishment of the thermocline takes place, the dam will continue to produce exceptional, challenging fishing to those who are prepared to put the effort in”.

For anglers this means it will be a time to catch barra again in Awoonga with all the reliability for which Awoonga is known.

Facts

The breeding process

We really do not know how lucky we are in the south of the state to have GAWB producing quality barramundi fingerlings like they do. They supply almost 100% of the barra fingerlings to areas south of Mackay so there is more than a fair chance if you have caught a barra, Kurt and the GAWB Hatchery team were responsible for it being available to you. For that alone they deserve a big pat on the back!

When we visited the hatchery I took great interest in seeing first hand how the barra are bred and the effort that goes into producing a viable number of fingerlings for release. So let’s look at the process to give everyone an insight into what makes their barra fishing world class fishing.

The first stage of the process is the collection of brood stock. These fish are collected from wild stock every year or so to ensure the genetics of the fingerlings are varied and the same two or three parent fish are not producing all the fish.

The barra are then placed into indoor tanks and light triggers are used to trick the barra into believing the time is fast approaching for spawning. The female fish are spot checked for ripeness of eggs and when their eggs reach a given size, the females are induced with hormones to make them spawn at a known moment in time. This is important as you do not want the females releasing eggs when hatchery staff are not ready for them as it will lead to unviable eggs and possible water quality issues.

At the given time the male barra will release their milt to encourage the females to drop their eggs. About an hour later the females release their eggs and the males again release their milt over the eggs, fertilising them.

The eggs float and can easily be collected by hatchery staff where their viability is assessed. If it’s less than perfect, the entire spawn is destroyed. This ensures only quality fingerlings are produced. The spawn event occurs over three consecutive days.

Once the eggs hatch, the fry are fed on specially prepared plankton and phytoplankton. This food is bred on site as it’s the only way to ensure enough is produced to feed the ravenous hoards of fingerlings. A typically successful spawn will yield around 1.5-2million fry. A 1.8million fry spawn occurred two days before we arrived.

The fry are grown out to around 50mm in six to eight weeks and are then ready for release into the various waterways.

From release to legal size of 58cm it takes around 12 months. Not very long and a really quick turn around in terms of released fish coming into the fishery for anglers to catch.

Facts

The numbers game

Fish stocked since 1996 (excluding 2010 stocking)

| Species | Number |

|---|---|

| Barramundi | 2,785,348 |

| Sea mullet | 471,608 |

| Yellowfin bream | 78,003 |

| Saratoga | 52 |

| Mangrove jack | 57,942 |

This is a typical shot of the numbers of barra that are stacked up in Awoonga at the moment. As water chemistry and clarity improve, these fish will come on the chew big time.

A very small part of the 1.8million barra spawned just before we arrived. These fish will be ready for release by mid to late April.

The Boyne River has been inadvertently stocked with thousands of big barra that are accessible to every angler. Steve Morgan puts some finishing touches to another metre-plus fish.

Escapee barra are being caught downstream of Awoonga in the Boyne River. Steve Morgan with another metre-plus barra that snaffled an Asakura boney bream imitation.

Stephen Booth putting the hurt on a Boyne River barra, or is it the other way around. Even this 6-8kg Quantum Accurist rod and Quantum Energy PTs reel were tested on these fit escapee barra.

The Bushy Stiffy Minnow is as good a lure as any we found to target the Boyne River’s barra.

The spillway makes a stunning backdrop to the fishing stage. Steve Morgan and Kurt Hutchby do some stock assessment. Well at least that’s the story we are sticking with anyway!

Tired and happy. The stock assessment was completed and the results showed most of the big barra have left the spillway through the escape channels. They are now in the Boyne River and providing lifetime highlights to many anglers.

(with fact box Awoonga into 2011)

Checking out the culture ponds that feed the fry. It’s an incredible system that allows an amazing success rate and consequently plenty of barra for stocking.

The brood stock are kept indoors and the light duration monitored to get the breeders ready for their part in the stocking program. Here Steve Morgan is hand feeding some of the brood stock. And yes he still has all his fingers – just!

The Awoonga spillway was still flowing over in late February. This photo clearly shows the escape channels GAWB staff built to release the trapped barra into the Boyne River downstream. A raging success.

Here QFM editor Stephen Booth is assessing the stock of trapped barra below the spillway at Awoonga. And if you wanted to know how good the fishing was, well it was simply brilliant.

The fish that went over the top are now fit, healthy and their battle scars from the trip over the spillway are healing very nicely.

This barra, caught below the spillway, was released to travel down the escape channel and joins its brethren in the Boyne River to terrorise baitfish and anglers alike.

Steve Morgan dealing with a leaping barra. There is little doubt the fish that escaped and survived are fit and full of fight.

This barra of around 110cm snaffled a Nories swimbait in the spillway pool.