I have fished freshwater in the north every year for a quite few years, and during that time I have picked up some tips on how to stay alive in crocodile country.

On our first trip we travelled to Lakefield National Park, which was my first time camping in the northern bushland. My fishing companion, my brother-in-law Wayne, was a Cape local and he was only too keen to show an old Brisbanite like myself the best fishing haunts the north had to offer. But before we headed off Wayne gave me a run down of the warning signs to avoid crocodiles.

We had an early start to the day, up at 5.30am. After two hours of walking the bank casting lures, it became very hot and very humid, especially for a southerner. Wayne unfazed by the heat charged a 100m in front of me; and my 2m stature is defiantly a disadvantage when negotiating the low lying riparian foliage. Nevertheless, I was determined to land a big barra: I had to outdo Wayne with our ‘first, biggest and most’ bet, which had become a tradition.

Eagerness fuelling an overheated brain, I searched for likely looking snags to cast to without hanging up on the foliage around me. Above on a high bank I could see deep water with a 2cm thick twig protruding the water’s surface. I scrambled down to even, flat ground and began casting the Gold Bomber past it, winding in slowly for a nice swaying body roll that sent off reflecting flashes of golden light. An intermittent jerk spiced the retrieve up a little.

After about six casts, with Wayne’s previous taunts of “Why bother with little bass when you can come up here and catch big barra?” still reverberating between my ear holes, I started feeling strange and apprehensive. I looked around and realised I had put myself in the very position Wayne had warned me not to. I was on a narrow strip of only just dry land. Behind me was a steep slope with a 70 degree angle. The slope I came down was at about 45 degrees of hard baked earth with a layer of dried leaves. In front of me was deep water, and I couldn’t see the bottom.

By this time I had stopped winding and my Bomber floated up beside the twig. My brain was now thumping me from the inside shouting at me to “Go!” I wound in that lure as fast as I could. An explosion of water just a few metres in front of me scared me out of my wits. My first thought was “Croc – I’m dead”, until I saw the bronzed body of the largest freshwater barra I had still ever seen. It was powering away from me with my lure in its mouth. My 10km braid pulled tight, I was in such shock that I did not even think to fight the fish. With a drag set too tight for such a big fish it busted me off on the twig. Rather than lamenting losing the fish, I was just thinking how lucky I was that it was a fish that caused the commotion and not a croc.

Fully panicked, heart throbbing in my mouth, I scurried up the slope I came down, only to lose traction on the dry leaves. I slid back down 2m that I made on the 4m slope. I threw my rod up the bank and climbed up with my now two free hands, brushing aside the leaves to gain hand holds. My feet pushing me upwards only gaining traction on the spaces cleared of leaves by my hands. I obviously did not have an effective escape route.

I had broken some of the basic rules that Wayne had previously told me. I was too close to deep water and could not see the bottom of it. I did not have an effective escape route. I did not remain fully aware of my surroundings. The only thing I did do right was to listen to my sixth sense – eventually.

When I say ‘my sixth sense’, I mean the warning feelings you get when something is about to happen. We often hear people say, “I had a bad feeling about this…” when they explain an incident while doing nothing out of the ordinary in their normal lives.

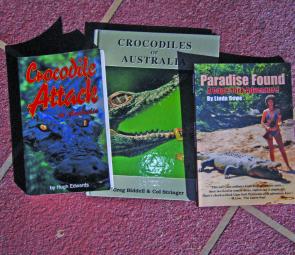

This is adequately explained by retelling part of a discussion I had with Linda Rowe recently. Linda owns The Croc Shop, a souvenir shop in Cooktown, and has spent a very adventurous life on the cape. Linda has written about her early days on the cape in a book called Paradise Found – A cape York Adventure. She had an incident that doesn’t appear in her book, as it happened just a few years ago.

Linda had finally found reliable directions to a very unfrequented waterhole that was starting to take on mythical status with her. She parked her car and walked with her German Sheppard the last 5km through scrub and long grass to the lagoon. There were not any tracks to follow, not even an animal pad. As she approached within 5m of it, alarm bells started ringing. As she turned away, a huge croc erupted from the water, grabbing the dog in a straddle length ways. She was being dragged while holding on to the lead as the croc turned and made its way back to the lagoon. With a fallen log in its path, the croc threw the dog into the air and raced to meet it on the other side. At this moment, Linda heaved on the lead, pulling the dog back to her. She picked up the injured animal and ran.

The dog survived with a series of puncture marks on its back and underbelly. Linda still doesn’t know what gave her the willies, but is certain that if she didn’t obey them, then things would have been a lot worse.

There are a few well known common sense things of what to do and what not to do in croc country. Things like ‘don’t swim unless it is signed safe to do so’, and ‘don’t camp too close to the water’, or ‘don’t dump food scraps or fish remains in the water or close to boat ramps or camp sites’. As anglers, there are a few other tips to consider. Things like ‘only enter shallow water if you have clear vision of the bottom and there is a large area of shallow water’.

Whenever Wayne and I fish such regions, we always fish together and we have our own patch to watch. Obviously, if you counted three logs in your area and then there is suddenly four logs – then don’t hang around.

You must remember that crocs have good eyesight, good hearing and a good sense of smell and are fast with very good camouflage and stalking abilities. Therefore, we have to remain ever alert and ever aware and don’t take chances. The main dangers are complacency, being unaware and ignorance.

Once I was fishing from a sand bank in the tidal, but freshwater reaches of the upper Annan River outside of Cooktown on foot. The water was deep and relatively clear close in but I still couldn’t see the bottom so I stood back from the edge by 2m. A huge greyish shape slowly rose straight up out of the depths to about 1m from the surface. It only stayed there for a few seconds, then melted away by slowly sinking again. I have no doubt that I was being stalked, I didn’t hang around. You have to remain forever vigil.

On another occasion, I was drifting past the mouth of a small creek opposite the King Ash Bay camping grounds near Boorooloola, NT. My mate Garry and I watched a small 50cm long crocodile slip off the bank of the creek, swim its breadth, track our drift on the bank, enter the water to intercept our tinny at the bow. What it was going to try to do to us I don’t know as we are both close to 2m tall. Crocs start stalking straight at birth and this one was obviously very ambitious.

Another time at the Annan River, this time at its mouth, I came across a pro-fisherman’s camp. A pole of the lean to that served as the general living area was in the water of the high tide. The two tents of each fisherman was about 3m from the high tide. I stopped and spoke to a young man in attendance. I learnt that he was new to far North Queensland having arrived a week beforehand from Perth. As I sat with him, away from the water, I explained how dangerous his camp was. I pointed out to him a big croc slide just across the river, and even had to explain to him various basic items like the sharp gill covers on a barra. His employer was obviously very lax in teaching him anything at all. Two hours later the tide receded exposing the filleted frames of the previous night’s catch and I had to ask him the question as to whether his employer liked him at all.

I saw this young man two days later in Cooktown. He was employed by another fisherman who was truly professional. He had stayed for three days in the previous camp - on borrowed time.

The next point to consider is how you approach the water. By this I mean: do not present yourself as an easy meal. Try to keep some sort of physical barrier between you and deep water, a barrier, such as distance, a high bank or a tree (preferably two trees as this gives less options for angles of attack). If collecting water from deep water, then use a bucket on a rope and remain aware. It is best to have someone else with you as a second set of eyes. Once you have your water, then move off.

If the bank is a gentle slope to the water, then pick a large shallow, clear area. Make sure there is good visibility into the water from glare, shadows and leaf litter. Make sure you know what is in the water, study it for a while. If you are not 100% certain of this area, then find another.

As animals, like pigs and kangaroos, habitually frequent the same drinking location it would be prudent not to linger in these areas. Re-consider a camp site if a party has only just left as you would most probably use the same fishing and water collecting locations as they had.

A few years ago, Wayne, myself, and a few mates were camping on a high bank by the North Kennedy River in Lakefield National Park. In the four nights that we were there, we had two shrimp traps go missing (cherabin shrimp are a delicacy). We also had a large volume of water erupt bank side one evening just 50m up river. Two nights later it happened again 50m down river. This time it was followed by frantic squeals as something was dragged into the water. That whole episode took less then a minute. It was only the previous day that we had observed a fisherman from another camp, sitting on a rock in this area, with his feet almost in the water.

Wayne learnt later that this camping area was closed off due to Steve Irwin and his team placing a GPS tracking device on a particularly aggressive 5m+ crocodile.

Remember that crocs have a very fast short burst swim and short burst land speed. I am reluctant to quote speeds as different sources of information give varying accounts. One thing is for certain though, their speed capabilities are a lot faster than a human’s.

Beware of being stalked and don’t stay in an area too long, a crocodile has a faster learning capacity then a lab rat. A 5m crocodile only has a brain the size of a walnut, but it uses it very effectively at working out its prey’s patterns. As they can stay submerged for up to five hours, they have time on their side to observe, learn, predict and set a trap.

Cast nets are a great way of bait gathering, however, the noise of the net hitting the water, the struggling of the catch in the net, half dead by catch thrown back in, all tends to attract attention. The next person dragged into the water by throwing the net over a stalking croc won’t be the last. Consider having the loop at the end of the rope around the fingers and not around the wrist as this makes it easier to slip it off. Needless to say, you will most likely still be going in for a swim.

Other tips include: -

• Carry a little hand held UHF radio. They are getting cheaper with longer ranges all the time.

• Don’t fish alone, leap frog every second spot so you both get a good bash of the area. When doing this you should both carry a 4m length of stout rope with a knot in each end that acts as hand holds. If somebody falls into the water, then this is a quick and effective means of helping them out.

• If you do go for an unexpected swim, then don’t panic and swim slowly (preferably using breaststroke). Crocs hone-in easier on frantic water disturbances.

While I might sound paranoid with this article, I don’t believe in taking needless risks. The saltwater crocodile of the Indo-Pacific region is an especially aggressive critter and deserves respect.

I don’t believe in the unnecessary killing of these animals as they are an integral part of the environment. There is a direct correlation between the croc and barra population in a river system: crocs keep the catfish numbers down that prey on the young barra.

I do believe in the management of the crocodile population through possible safari style means. This would bring financial benefits to the local area as well as solving ‘problem’ animals. The relocation of these problem crocs doesn’t work as they return to the area that they were caught in. Examples of this is crocs from the west side of the Cape York have returned home after being re-located to the east side.

One possible solution was told to me by Linda Rowe. She was talking to a New Guinean who told her that they are allowed to hunt crocs up to 10ft. Over that length they are protected. The crocs that survive learn not to mess with humans and avoid them. This is evidenced by crocodile hunter’s stories how quickly a river seems devoid of crocs once hunting started in it. Maybe we could partially adopt an approach like this, limiting the amount of smaller crocs killed in an area by safari style hunting?

Overall, when in croc country remember to always remain alert and informed. The main victims of a crocodile attack are those complacent, ignorant or fool hardy.

Reads: 8376

This particularly aggressive crocodile was around 16-18ft.

Where crocodiles are found, the indigenous people use them in their art forms as they are linked to their mythology. This is a painting from near Darwin, the three wooden carvings are from different areas in New Guinea.

The crocodile trap at Lakefield National Park ranger’s station.

A small freshwater crocodile in the Normanby River.

A foot print of a large croc with a Leatherman tool for scale. We didn’t see any crocodiles at this waterhole, but they must always be expected.

Rod Whyte with the results of walking the bank. Notice how high above the water the camp is. A physical barrier like the height of a bank is essential when choosing a safe camp site.

Wayne Brennan with a barra caught walking the bank. Just behind him is where a large crocodile attacked something early one evening during our stay.

Wayne fishing a hole in the Normanby River. He could have been a little further back from the water’s edge but as the water was shallow he was relatively safe. There is debris in the water near the edge, so he was watching for any sign of movement. Also n

Books that are good sources of information. Do your homework and research the area you are visiting.

Take note of all warning signs. It is amazing how many people disregard these signs at their peril and found this out the hard way. Always use these tips when in croc country.